Let’s start with environmental context when learning about our White Salmon history

and historic places. This research and documentation was created as part of the

City of White Salmon’s 2040 Comprehensive Plan.

The city of White Salmon lies in a transition zone between the maritime climate

west of the Cascade Mountain Range and the dry continental climate of the

intermountain region to the east. This transition zone is characterized by mild, dry

summers and cool, wet winters. White Salmon is sometimes called the “Land

where the sun meets the rain.”

Successive floods, the Bretz or Lake Missoula floods of the late Pleistocene and

early Holocene Epoch, scoured the land in some areas and deposited sediment

elsewhere. The central city of White Salmon is situated on a bluff approximately

550 feet above the Columbia River. The city also includes approximately three-quarters

of a mile of river frontage, including two established fishing sites under

tribal jurisdiction. The area’s geologic history and climate greatly influenced

White Salmon’s pre-contact and post-contact culture and history.

Inhabitants

Humans have inhabited the Mid-Columbia Plateau and Columbia River basin for at

least 12,000 years. The earliest peoples developed diverse cultural patterns and

several subdialects of the Sahaptin and Chinookan language groups. A common

bond among Mid-Columbia inhabitants was the Columbia River, an artery of

commerce and cultural exchange and its natural resources. The abundance of

salmon was central to the life cycles of early inhabitants.

Over time, the population of the Mid-Columbia region shifted from a huntergather

subsistence pattern to more settled villages beginning around 4,000 years

ago. One of the oldest known settlement sites in the area, south of Klickitat County

in Oregon, dates to 9,785 years ago.

The four tribes with treaty rights within the area include the Yakama Nation, Warm

Springs, Umatilla, and Nez Perce. Locally, tribal people fished for salmon in the

rivers, hunted game in the upland forests and meadows, and harvested food and

medicine in the prairies. Within the Mid-Columbia region, lithic sites, rock cairns,

huckleberry trenches, quarries, camps and villages, and pictographs and

petroglyphs are physical evidence of the long relationship of the native

people to the land.

Prior to contact with Euro-Americans, the upper Chinookan people resided in oval

or circular pit houses. Constructed with a roof of poles, brush, or mats and partially

sunk into the earth, some circular pit houses could be up to 50 feet in diameter

and 12 feet in depth. In Klickitat County, a good example of a pit house village is

the Rattlesnake Creek Site located on Department of Natural Resources lands

north of Husum. More than 2,000 archaeological sites have been recorded in

Klickitat County.

The earliest written evidence of contact between Euro-Americans and the

indigenous population in the White Salmon area, the journals of Lewis and Clark,

indicate a village near the river that Lewis and Clark named the White Salmon

River. The Corps of Discovery members observed multiple subterranean structures

with conical roofs as they traded with the native population who spoke an Upper

Chinookan dialect.

White Salmon History: Early Settlers

After the Lewis and Clark Expedition’s brief 1805 and 1806 visit to the White

Salmon River, direct Euro-American presence in the area was limited. In 1843, the

first wagon caravan of 900 emigrants reached The Dalles in the Oregon Territory;

however, most early Euro-American settlers journeyed to the fertile Willamette

Valley. In 1853, Erastus and Mary Joslyn, traveling downriver by steamboat,

disembarked at The Dalles. Later, they continued downriver and spotted fertile flat

land on the north bank of the Columbia River in the Washington Territory,

approximately one mile east of the White Salmon River, and purchased their

homesite from the Klickitat Tribe. After the Klickitat Tribe moved onto the Yakama

Reservation in 1855, Euro-American settlement accelerated. In 1867, Mary’s

brother James Warner arrived and established a post office. In 1874, A. H. and

Jennie Jewett arrived and settled on the bluff , today’s White Salmon. The Suksdorf

family arrived the same year and settled on the flatland along the Columbia River,

now Bingen.

Early Development

Agriculture and natural resource extraction drove the early local economy. Early

inhabitants of White Salmon and the surrounding area raised cattle for the eastern

mines and harvested timber to fuel the steamboats. (HRA 1995 and McCoy 1987).

Wheat farming and salmon harvesting also built the local economy. The Jewett

family are often credited with being the catalyst of the renowned White Salmon

Valley horticulture industry. The Jewett’s nursery and resort became a nationally

known showplace for visitors. The Jewett family was instrumental in development

of the City’s water system, and they made donations of land for Bethel Church.

A ferry provided transport service between the White Salmon settlements, and

Hood River, Oregon. The community constructed the Dock Grade Road to the

Palmer Ferry Landing west of the present-day approach to the White Salmon-

Hood River Bridge. Horse-drawn wagons transported cargo and passengers to a

flight of stairs that led up the embankment to the town of White Salmon.

In the early twentieth century horticulture, particularly raising fruits and berries,

was an important economic driver in the area. A combination of horticulture,

railroads and roads, and land speculation led to the “Apple Boom” of the 1910s.

(Patee 2016) As prosperity increased, so did discord among the upland and

lowland families resulting in the construction of what today is known as Dock

Grade Road. The questions of the day included where the roads, railroad, post

office, and water source should be built – close to the river or on the upland.

Theodore Suksdorf platted Bingen in the lowlands in 1892. Bingen opened its

post office in 1896. Mr. Jewett platted White Salmon and the town became

incorporated in 1907.

20th Century Trends

The Spokane, Portland, and Seattle railroad came through the Columbia River

Gorge in 1908 with a stop at Bingen. Was the station to be named after Bingen or

White Salmon? The compromise was to name the ”Bingen-White Salmon“ railroad

station after both towns. Thereafter, the two cities, Bingen and White Salmon,

grew side by side but at different elevations. That same year electric lights came to

White Salmon, along with the first fire hydrant, and in 1910 the first sidewalks were

built. The Condit Dam on the White Salmon River was completed in 1913 and

provided electricity to the area and as far away as Camas, Washington.

The Klickitat County government began planning the current road connecting

Bingen and White Salmon, now Washington State Route 141 (SR14), in the 1910s

and local volunteers, under County supervision, began construction of the road in

the 1920s. The Hood River Bridge over the Columbia River opened in 1924. SR

141 provided a vital link between the Columbia River and interior locations of

Trout Lake and Glendwood. SR 141 became to be known as White Salmon’s Main

Street. SR 141 Alternative now bypasses downtown White Salmon and serves as a

principal corridor to the inland recreation areas near Husum, Trout Lake, Mt Adams

wilderness and recreation areas, and the Bird Creek Meadows on the Yakama

Reservation. The economic history of White Salmon has been driven by canoes,

trails, ferries, steamboats, trains, and roads.

In the 1970s White Salmon civic leaders, perhaps because the Suksdorf family had

named the settlement Bingen after their ancestral home of Bingen am Rhein15,

were attracted by a minor national trend of revitalizing a community by adopting

an architectural theme. The faux Bavarian theme seemed to work well in

mountainous Leavenworth, WA so why not in White Salmon, too? While

Leavenworth succeeded in drawing tourist to its theme park-like town, White

Salmon did not fare as well. Only a few buildings retain any faux Bavarian design

Congress passed the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Act (Act) and

President Ronald Reagan signed the Act on November 17, 1986. The Act mandates

the protection and enhancement of scenic, cultural, natural and recreation

resources and the protection and support of the Gorge economy16. The Act

designated a total of 292,500 acres for special protection on both sides of the

Columbia River from the outskirts of Portland-Vancouver in the west to the semiarid

regions of Wasco and Klickitat counties in the east. The Act created 13 urban

exempts areas including the White Salmon/Bingen Urban Exempt Area. Most

residential and commercial development within the Columbia River Gorge

National Scenic Area is encouraged to take place within one of the 13 designated

Urban Exempt Areas.

White Salmon, since the late 1990s, has become a destination for recreationists

and tourists. The community offers all city services and provides retail, medical,

cultural, educational, and recreational facilities. The community of White Salmon

has grown from its birth in 1907 and has established itself as a vital part of the

Columbia River Gorge.

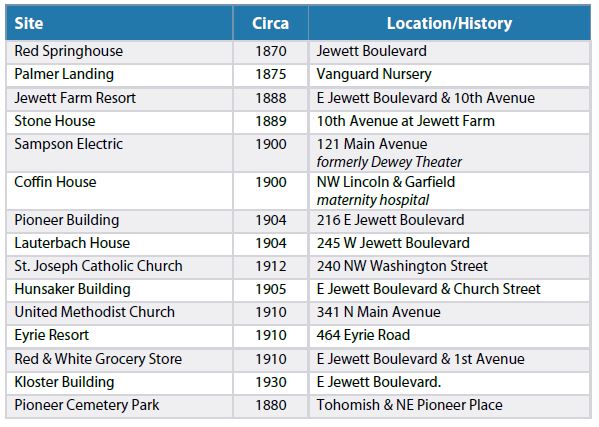

Local Resources of White Salmon History

Historic and Cultural Sites and Structures

Community members are proud of White Salmon’s cultural heritage and history.

To preserve and share that heritage, citizens of White Salmon and West Klickitat

County established the West Klickitat County Historical Society in 1984. The

Society’s collection of data, artifacts, and pictorials are housed in the Gorge

Heritage Museum, formerly the Bingen Congregational Church (circa 1912).

The West Klickitat Historic Society and knowledgeable community members

consider many late nineteenth and early twentieth-century buildings to be of

local historical significance. The White Salmon 2012 Comprehensive Plan

identified several notable locally significant buildings.

Evolving Inventory of Historic and Cultural Resources

Local Historic Resource Strategies

Many communities have adopted historic preservation programs which include:

• a methodology for conducting a local survey of historic or cultural resources;

• criteria for establishing local historic or cultural significance;

• creating a City-administered preservation commission or committee; and

• adoption of an historic preservation ordinance.

White Salmon could employ such proactive strategies. Until such time, however,

identification of historic resources in White Salmon will be based on guidance

and programs developed by state or national agencies, or what someone locally

thinks is old and of historic intertest. Creating a more robust historic and

cultural resource preservation program requires a commitment from the

local government, dedicated local supporters, and the guidance of

qualified professionals.

The Washington State Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation

(DAHP) is the primary state agency supporting historic preservation and

cultural resource programming. DAHP is an excellent resource for

professional guidance on:

• Historic building survey and inventory;

• Archaeology survey and inventory;

• Model historic preservation ordinances;

• Historic research and building review;

• Historic Preservation law;

• Certified Local Government (CLG) program; and the

• Main Street program.

Evolving Historic Resources

History evolves and what was once new or familiar may gather historic or cultural

significance over time. Consequently, the inventory of historic resources changes

and expands through the years. Best inventory practices are for a community to

reevaluate the local inventory each time the community updates its

comprehensive plan.

The George and Louisa Aggers House, 464 SW Eyrie Road, known as “Overlook,” is

in the Urban Exempt Area. In 2020, the property was listed in the Washington

State Historic Register17. Overlook was once part of a small 46-acre cherry orchard

business on the western edge of White Salmon. The 1910 craftsman style

farmhouse serves as an excellent example of Arts & Crafts dwellings from the early

twentieth century.

White Salmon is also home to a notable collection of early to mid-twentieth

century commercial and institutional buildings, several of which were designed

and constructed by Day Walter Hilborn, one of the most prolific and important

architects in the history of southwest Washington State19. Hilborn is credited with

at least seven commissions in White Salmon, including the White Salmon Post

Office (1941), B.O.E. Elks # 163, Bethel Congregational Church (1947), a movie

theater, rodeo grandstand, and several private residences.

The Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation

(DAHP) maintains an inventory of historic and cultural resources. Some of the

properties are eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).

See Appendix A, White Salmon Area Inventory of Historic Resources, DAHP –

Select. Currently, there are no properties in White Salmon listed in the NRHP;

however, investigation by DAHP representatives has determined that several

historic resources may be eligible for listing in the NRHP.

The importance of periodic updates to the historic inventory is illustrated in

Table below. A decade ago, the community might not have considered the cluster of

residential dwellings to have architectural significance. However, in 2020 a team of

qualified historic and architectural professionals prepared Historic Property

Report(s) for these residences and concluded that the cluster of houses may be

eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places because of the local

architectural character.

Click Here to Print this Document: White Salmon History and Historic Places